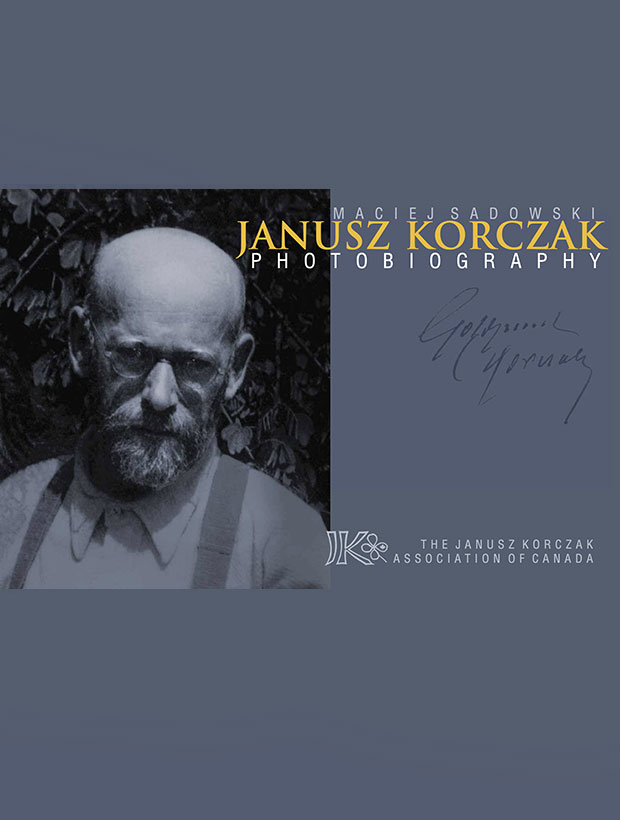

The book Janusz Korczak, Photobiography published during the year of the celebration of life and legacy of this great man is a special one; an album printed on elegant, high quality paper with a hard cover, a beautiful dust jacket, and a silk bookmark – it beckons as a wonderful gift for many of Korczak’s followers and admirers.

The album, which was created by Maciej Sadowski, an artist and researcher, is the second undertaking of his in the same unique genre – a biography shown through photographs. The first was a Marie Sklodowska-Curie album, which was published in Warsaw in 2011. Both of these volumes are the author’s true labours of love.

I was pleasantly surprised that Maciej Sadowski chose for the cover of a new book not Korczak’s iconic photograph taken by Edward Poznanski in the 1930’s (the image which, unfortunately, was overused by the designers of numerous books on the Old Doctor (Ill. 1)), instead, the author opted for a different picture taken in Palestine in 1934, which actually is an enlarged fragment of the group photo of Korczak with former residents of the Home for Orphans (Ill. 2). This lesser known photo simply asks the reader to take a closer look. Isn’t this a wonderful idea?!

Over one hundred images were included in the album. Working on the selection, Maciej Sadowski collected an even larger number of them, which must have been quite an undertaking. Impressive indeed is the list of institutions that the author dug through in order to gather these pictures: The Museum of History of the City of Warsaw and its chapter Korczakianum – The Korczak Centre for Research and Documentation, along with the Emmanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, Ghetto Fighters’ Museum in Israel, Polish National Library, Warsaw Public Library, and the Archives of the Warsaw Atheneum Theatre.

The photos are arranged according to chronology, typical for Korczak’s biographies: 1878 – 1904, 1905 – 1918, 1919 – 1931, 1932 – 1939, 1939 – 1942, thus portraying childhood, university years, work as a pediatrician and later on as director of the Home for Orphans. His publications and social activities were mentioned, as well as his military service during the wars and ultimately, the tragic events of WWII.

The Korczak iconography is not a field of my expertise and I would not dare to judge whether the collection of the pictures presented in the album is exhaustive. No doubt, however, both – the most representative and those familiar only to a small group of Korczak specialists – were included in the album.

The way that Maciej Sadowski used the iconographic material shows his unquestionable refined artistic taste and fluency in modern photo technology. He remastered the old photographs (the earliest of which, the post card of Warsaw, is dated around 1870) with utmost care and respect. Many are shown in full size along with enlarged fragments – a technique that invites the readers to give their all to each detail of the picture. I assume this is the first time such an opportunity was afforded.

Among the photographs presented in the book, there are the portraits that had been taken by professionals, some most likely in the studio, such as a the ten year old Henryk Goldszmit (later Janusz Korczak), a well known picture that had been used as a frontispiece in the original edition of the book King Matt, as well as in most of the following editions. Then, Korczak’s portrait boasting the student’s uniform of Warsaw Imperial University, another from the 1920s and one later from the 1930s. Finally, we behold one taken for the questionnaire completed on the order of the occupants in September of 1940. That is all. Maybe Korczak didn’t like to be photographed, just as he didn’t like to be interviewed or be in the centre of public attention…

Other than those few, in the album there are pictures of Korczak with his colleagues and friends. One with his fellow educators at the summer camp of Wilhelmowka in 1908 (most likely, this excellently ‘staged’ photo was taken by an amateur (Ill. 3).) The other one: Korczak among the members of the Help the Orphans Association, with his close friends Isaac and Stella Eliasbergs (1918). Unfortunately, Stella (wife of the President of this Association, and after his death its Vice President) was wrongly indicated on the picture [*1]; Stefania Wilczynska (who was, along with Korczak, a key figure at the Home for Orphans) was not indicated at all (Ill. 4) [*1]. Yet another photo: Korczak with Maria Grzegorzewska and other professors at the Institute of Special Education (1925/1926) whose names are unknown but whose faces tell their own tale. Finally another photograph of Korczak with Isaac Eliasberg and Stefania Wilczynska (Ill. 5).

Photobiography provides graphic evidence of Korczak’s time as well: The portrayal of the city of Warsaw that Korczak loved so dearly, the University library where he spent long hours preparing for the exams, the Children’s Hospital where he started his first job as a physician, the street cars, which he may have run for in order to make it to the Home for Orphans or to Our Home (an orphanage for Polish, non-Jewish children) on time, or perhaps to meet with a publisher or start talk at a radio station... There are also images of other European capitals where he continued his studies in both medicine and education. Then, the images of the Russo Japanese war (1905) where Korczak would for the first time be witness to the horror of destruction. His destiny was to experience the terror of war not once, not even twice, but four times.

Even more insight into the atmosphere and style of the era is provided by inclusion in the album covers of the original edition of Korczak’s books and magazines where he published his stories in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s.

However the most precious photographs in the album are those that present Korczak with children. Simple, spontaneous and authentic, they were taken by amateurs, most likely Korczak’s young assistants or former residents of the Home for Orphans who just seized the moment and clicked the shutter. In these photos, Korczak is surrounded by Jewish children and Polish ones, some of them happy and joyful, the others serious or just quiet – each picture of the individual. Korczak is rarely the focal point of these pictures (Ill. 6, 7, 8). Sometimes it is even hard to find him, hidden in the corner of this crowd of kids. To look at these photos over and over again is a sheer delight. At the same time, it is painful, as so many of the children in these shots perished during the Holocaust. We look at their young faces and see the grim face of history awaiting Polish Jews during WWII.

Captions for the pictures are borrowed from Korczak’s works: from his Ghetto Diary, How to love a Child, An Educator’s Prayer, as well as from his letters to his former pupils and Commemorative Postcards handwritten by him that residents of the Home for Orphans received for their achievements. These highly apt comments perfectly complement the photographs. Such a precise ‘montage’ results in capturing the authentic image of Korczak.

The album is a bilingual Polish English edition.

A welcome addition, indeed. It could make for interesting reading not only for Korczak scholars (who for the most part know Polish) but also for those about to embark upon their maiden voyage for Korczak’s world. This is especially important, as Korczak’s life and heritage are not very widely known in English speaking countries, both in the US and even less so in Canada. The album was therefore a great opportunity to disseminate Korczak’s ideas “across the wide seas”. However, in or der to achieve this goal, high quality English translation was a must. With regret, I have to admit that the translation is a far cry from the required standard; it is, in fact, the weakest point of the whole publication.

No efforts were made to adapt English captions for the non-Polish readership. This is especially true of the Calendar of Korczak’s life, which was placed at the end of the book. The mediocre and sometimes awkward translation becomes an obstacle between Korczak and those readers who are not familiar with the educator’s ideas and realities of life in Poland in the first half of the 20th century. Meanwhile, just a few additional words would provide the reader a useful hint resulting in perfectly understandable and less confusing wordings.

Moreover, there are some absolutely unacceptable mistakes that surprise or even shock the reader. For example: in a very important note from Korczak’s Ghetto Diary about the authors who would have influenced him a great deal, forming his social views and literary work, he wrote: “Of all writers, I owe the most to Chekhov – a brilliant diagnostician and social clinician”. In the English translation, however, the famous Russian novelist Anton Chekhov, (a name which is recognizable for the English speaking reader) becomes Czechowicz! Jozef Czechowicz (1903 – 1939) was an avant-garde Polish poet, known for his catastrophic and oneiric vision. Czechowicz died tragically, a few days after WWII had started, on September 9, 1939, during the bombardment of downtown Warsaw. In such a case readers in the USA or Canada would be helpless even with Wikipedia at their finger tips! [*2]

Unnecessary misunderstandings are also caused by inconsistent attempts to translate Polish names into English. Having introduced Henryk Goldszmit (the real name of Janusz Korczak) as Henry on the initial pages of the book, the translator dropped this idea later on and returned to the traditional, “old fashioned” original spelling of the names, customary in English translation of Polish literature, forgetting to correct the spelling that had been used on previous pages. Let’s assume that the English speaking readers are smart enough to guess that Henry and Henryk is the same person (as are Jozef and Joseph or Izaak and Isaac) but what is the point of making them focus on solving this or other similar puzzles distracting them from the animus of the book and its narration: the thoughts and deeds of Janusz Korczak? Is there any reason to disorient the readers, providing them different translations of the titles of Korczak’s books on different pages? [*3]

Moreover, why not decide which name of his Orphanage is more relevant, at least out of respect for Korczak, instead of offering three versions of the name of the same institution? In summary, the English speaking reader of the album may well become involved in the process of translation instead of enjoying the fruits of its labours. Is this a new idea for a reality show in book format? In the context of a truly important book such as this, one intended to be taken seriously?!

Alas, when the reader has the book in hand, the appropriate time to correct inaccuracies and mistakes or in fact to attach Errata has come and gone. In any case, it is not up to the re viewer to make the relevant corrections. Rather, it is a matter of foregone opportunity not seized upon by the editor and proofreader upon whose embarrassed shoulders responsibility squarely rests.

[*1] The error has been corrected.

[*2] The name has been corrected.

[*3] All efforts have been made to use the original spelling of Polish names.

Having studied Korczak’s heritage for a good many years, I have come across many depictions of him: oil paintings, graphics, drawings, bas reliefs and even monuments. No doubt, each in its own way tells a story, but I have to confess that these images did not help me much to establish a real dialogue with Korczak. What was extremely helpful, though, was a close look at the old faded photographs of this extraordinary thinker. Maciej Sadowski, in his Photobiography, has granted me this opportunity. For the first time I have truly seen the eyes of a man who once said: “There are no children – only people”.

In September 2012, the album Photobiography was awarded The Warsaw Literary Premiere prize. During the ceremony, laudation was given by Jozef Hen, a former reporter from Korczak’s children’s newspaper, The Little Review, who is nowadays a recognized author. Wojciech Pszoniak, a famous Polish actor who played Korczak in Andrzej Wajda’s movie, recited selected parts of the text from the album as well.

Review of the printed edition by Olga Medvedeva-Nathoo