“I often found myself wondering how she always knew where to be at the right time. Whenever I got up to mischief, she was the first to know about it. And as soon as any of the children started to feel sad, she would instantly ask what was wrong. She’d produce their lost item from a pocket, and a handkerchief too, to wipe away the tears … The way she lived, we knew very little about her, she was so… So… non-existent. There’s nothing left of her, as if she were never here.”

Stefania Wilczyńska was born in 1886 in Warsaw, into an assimilated, well-to-do Jewish family. From 1906 to 1908 she studied natural and medical sciences in Geneva and Liège. She also took courses inspired by the German pedagogue Friedrich Fröbel, designed to train future kindergarten teachers. In 1909 she returned to Warsaw, where she asked for “an unrecompensed position” at the refuge for Jewish children situated at 2 Franciszkańska Street. There she met Dr Henryk Goldschmidt, who often called in there, and who had an interest in various educational methods. At the time he was working as a paediatrician at the Bersohn and Bauman Children’s Hospital, and had started to publish under the pseudonym Janusz Korczak.

Wilczyńska and Korczak had similar views on bringing up children, who deserved respect, trust and freedom, as long as no harm was caused to anybody else. At the children’s home that they ran, there was a set of rules in force which included a code of laws and duties for the staff as well as the children. There was a self-governing body and a court in operation too. Wilczyńska was in charge of keeping order – it was she who made sure the several dozen children had clean clothes without holes in them, were fed a healthy diet, got up early enough to wash and have breakfast before going to school, and then do their lessons, etc.

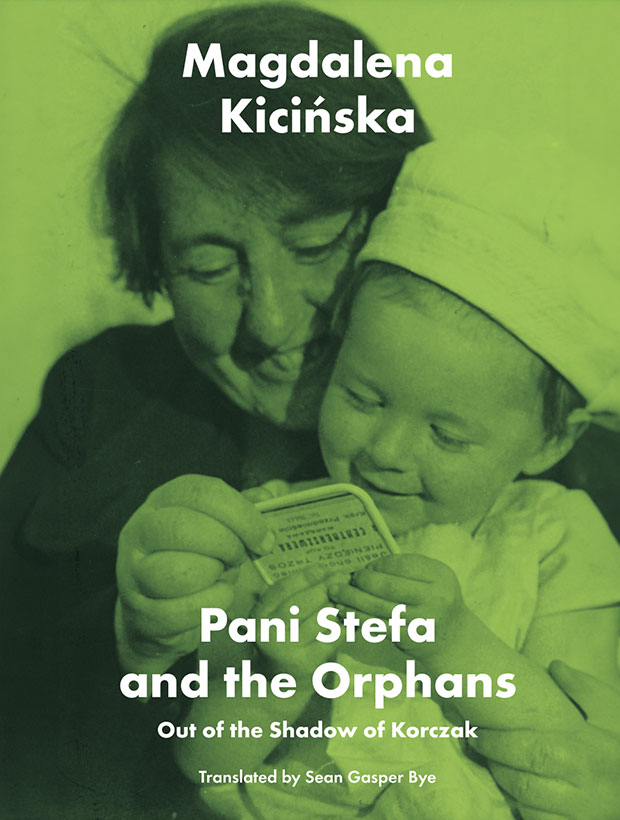

Those who grew up in her care remember Stefania Wilczyńska as a silent, austere person, always dressed in black, with short black hair and an inseparable bunch of keys. As Samuel Gogol remembered: “I don’t think she was cold. The children’s home couldn’t have existed without this extraordinary lady with the serious face. She took an interest in every little detail. The doctor wasn’t interested in things like our clothes, or whether our hands were clean and we were tidy. I think she substituted as a mother and a father for us, because somebody had to guide us with a firm hand. In my memories the home was Miss Stefa, and Miss Stefa was the home.”

She lived in Korczak’s shadow, and that is where she has remained. Many streets, children’s homes and schools have been named after him, and many monuments have been erected to him. They all show him at the head of a procession of children, apparently on their way to the Umschlagplatz, from where they would be forced into cattle trucks that would take them to the death camp where they would die in a gas chamber. Stefania Wilczyńska is not there with them, though everyone knows that she was. In May 1978, on the grounds of the former camp at Treblinka a stone was ceremonially unveiled to commemorate Janusz Korczak and the children. Among the 17,000 stones that comprise the monument there, it is the only one to have a name carved on it. Why couldn’t they find room to remember Stefania Wilczyńska there too? It’s a mystery.

– Katarzyna Zimmerer

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones